CMS strategy and requirements

Docs Planning

Table of contents

- Background

- Key Requirements

- Technical requirements

- Longevity

- Internationalization (i18n)

- Accessibility

- Content editing

- Versioning content changes

- Authentication for CMS editors

- Personalization

- Workflow and content approval

- Performance & full-page caching

- Security and Data Privacy

- Integration with 3rd party systems

- Forms

- Search

- CMS platforms

- What Studio 24 deliver

Background

As part of the W3C website redesign project, we plan to deliver a content management system (CMS) capable of managing content for high-level pages on w3.org. This document outlines the key requirements and types of CMS platforms we plan to evaluate. The decision on CMS platform will take place after testing a small number of options.

Key Requirements

Technical requirements

Key technical requirements include:

- Must run on Debian Linux

- Supports Nginx or Apache webserver

- PHP is preferred (PHP 7.3) as the underlying programming language for the CMS

- MySQL database is preferred, however other data stores can be considered

Longevity

Your RFP noted “We need a CMS that is long-lived and easy to maintain, because we run our systems for decades.” As we explained in our proposal, no software platform can claim to guarantee to be around in a decade’s time or more.

It is clearly challenging to recommend a CMS platform that will definitely be around in 10 years. W3C has a “bias towards popular software systems with large user communities (e.g. WordPress, Drupal, Mediawiki) as opposed to smaller projects with only a handful of users.”

The only truly stable format on the web is HTML, so one option would be to use a CMS that can output static HTML to be used on the W3C site. Static site generators tend to be newer software.

Another option is to use a Headless CMS approach to decouple the CMS from the front-end and lower the impact of any possible CMS change in the future (this is covered in more detail later on).

For the CMS software, we interpret this requirement as:

- A mature software product, ideally, one that has at least 2-3 major versions.

- Ideally the software should be open source.

- Software should be supported by a large and active community.

- Ideally, the CMS should have support for an API, so it is possible to extract content in a standards-based way, thus giving flexibility in the future.

Internationalization (i18n)

Internationalization is an important topic for a global organization such as W3C. From the Discovery phase we have identified a clear requirement for managing content in different languages for w3.org.

Initially, W3C plan to manage content for the following languages:

- English (American English)

- Chinese (Simplified Chinese)

- Japanese

- French (less of a priority)

Expected content for localised versions of w3.org is:

- Homepage

- Top navigation links (e.g. Standards)

- News (translations of W3C news where available, it is unlikely this will cover all news items due to available time & resources)

- Local pages, not on the main w3.org site (e.g. local news, contacts)

A CMS must support internationalization by:

- Allowing different versions of a page to be managed in different languages (e.g. translations for the About page)

- Support ways to flag when source content has changed so translated pages based on this can be updated (nice-to-have)

- Allowing new pages to be managed that only appear in one language (e.g. local news page)

- Support methods to switch between languages on the front-end

The HTML templates need to support bidirectional (bidi) content for:

- The full page (e.g. the full page is translated, e.g. a press release)

- Selected page content (e.g. a smaller part of the page content is in a different language)

For full page bidirectional text we need to consider how the design and page layout needs to alter. E.g. two-column content switching around based on primary & secondary columns. Richard Ishida, W3C Internationalization Lead, is available to support this work.

There is a preference to keep localised content on a w3.org URL.

Accessibility

It is a project requirement that the front-end is built with WCAG 2.1 AA accessibility at a minimum and ideally will meet AAA level accessibility.

However, CMS admin systems can be complex and use a lot of JavaScript to allow users to manage content. Due to this, many CMSs do not meet AA accessibility requirements. For example, WordPress has 189 open issues for accessibility for its new Gutenberg editor (as of 15 June 2020).

It is a requirement to use a CMS admin system that is accessible. However, it is not required to audit the CMS for accessibility or make changes as part of this project to fix any accessibility issues in 3rd party CMS tools (since this is outside the scope of this project). The W3C team can help confirm whether accessibility is good enough in a CMS.

Is it a requirement for the CMS admin system to be fully compliant with WCAG 2.1 Level AA?

Content editing

The CMS must be easy to use for the marketing team and enable them to manage content effectively.

Studio 24 designs sites using components to build up more interesting page content. It is therefore important that any CMS allows CMS editors to create content from a selection of flexible components.

This means the CMS must have:

- An intuitive editing tool

- Clear user documentation on how to edit and manage content

- An accessible editing tool

- Supports custom content fields

- Supports building content from flexible components

- A flexible templating system that allows us to write any HTML we wish, with no or little interference from the CMS

- Ideally, the CMS would support locking content once a user starts editing a page so that multiple people cannot accidentally edit the same page and overwrite each other’s work (nice-to-have)

Versioning content changes

Your RFP noted a requirement for “full change histories identifying who made each change.” Historically, W3C have managed many page changes directly in version control (CVS) so you are used to having a complete history going back decades. This can be useful in your day-to-day work when undertaking research.

As we explained in our proposal, it is highly challenging for a CMS to be able to replicate the full history and audit trail a version control system can achieve. Most CMS tools record a number of revisions rather than all of them.

Have a complete version history is nice-to-have and W3C are happy to adapt to what is possible.

There are two options to meet this requirement:

- Use a CMS that stores a partial history of page changes. It is acceptable to have up to the last 20 edits. However, it is preferred to store edits which represent published page changes - not micro changes which would undo the usefulness of this feature.

- Use a CMS that stores content in a version control system (e.g. Git), this would then give you the complete version history you are looking for.

Authentication for CMS editors

There is a requirement for users to login with their W3C account to access the CMS.

W3C use LDAP as an authentication backend for different services and associate roles in our services to LDAP groups. W3C have also looked at supporting OAuth, so this is a valid alternative if LDAP is not supported by the CMS.

Therefore, it is a requirement to support LDAP or OAuth authentication when logging into the CMS.

Personalization

It would be useful to introduce some level of personalization on the W3C site, however, this is nice-to-have functionality. For example:

- Display whether the user is logged in

- Display different content on a page if user is logged in (e.g. different messaging if logged in on Participate landing page)

On the new groups page some menu items are flagged as “Member-only.” If the user selects this link they must be logged in to view this page. This seems a good strategy for flagging member-only navigation links.

It’s important any personalization works alongside full-page caching via Varnish. Techniques to help with this include:

- Explore use of edge side includes

- Segment users into different groups (e.g. logged-in user, public user) and use Vary HTTP headers to enable full-page caching for each user segment.

- Use JavaScript for individual personalization (e.g. logged in name), this runs client-side so skips the cache. This can be achieved via XHR requests or via storing user data in the browser (local storage or a cookie).

- W3C have had issues with Symfony form submissions, that then redirect to a thank you page (to help avoid multiple submissions). Such pages are currently not cached since it is not possible to use flash messages.

- For any completely dynamic pages don’t cache at all (not recommended for high-level pages since it reduces performance).

Workflow and content approval

At a minimum, it’s expected W3C will have 10-30 people editing content on a new CMS, though this may be more. W3C has noted it would be helpful to have a simple workflow for adding new content.

Therefore it’s a nice-to-have requirement to have a simple workflow that allows some users to create and edit content but not publish, and others to be able to review content and publish.

Performance & full-page caching

Given the popularity of the w3.org site it is a requirement that any CMS used can support full page caching, via Varnish Cache Proxy, to ensure we can deliver fast and responsive pages to end users.

This means:

- Front-end pages are fully cacheable, which means they contain the same page content (and headers) for all users

- CMS can send a PURGE request to clear the cache when a page URL is updated

It’s important to be cautious of the use of cookies or personalised content that may restrict full-page caching.

Security and Data Privacy

It is a requirement for security to be a first-class citizen on the new website.

The CMS admin system and front-end website must follow security best practises (e.g. OWASP Top Ten and National Cyber Security Centre’s guidance on secure development).

The CMS must support two-factor authentication.

Data Privacy is also an important requirement for W3C. The website should be private by default. This means we will: \

- Adopt a “privacy first” approach with any default settings of systems

- Give users clear choices over data privacy

- Only process the data that is necessary to achieve your specific purpose.

We recommend avoiding tracking cookies and any 3rd party integrations that may set these.

Studio 24 has developed many client projects while taking the new EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) law into account. We’ve also written a number of blog posts to help educate clients about GDPR.

Integration with 3rd party systems

Your RFP noted a new CMS must “integrate with existing W3C-maintained back-end services (e.g. database of groups and participants).”

The point of integration is the front-end rather than the CMS itself. On the front-end there is a need to combine data from multiple sources to build page content.

For example, on the current homepage content is built from:

- News = read from WordPress /blog/news/

- W3C Blog = read from WordPress /blog

- W3C Member testimonial = read from Testimonials database (also displayed on https://www.w3.org/Consortium/Member/Testimonial/)

- Events = read from the Events Manager (also displayed on https://www.w3.org/participate/eventscal )

- Talks and appearances = read from WordPress /blog/talks/

Ways to achieve this include:

- Integration via APIs

- Writing plugins or template functions in the new CMS to pull in data from external sources

Forms

W3C use forms across the w3.org website, these are all currently custom-built forms.

Given the W3C Systems Team have expertise in Symfony web framework we recommend sticking with this approach of building custom forms in Symfony. It is easier to ensure you build what you need and can control security and privacy by building custom forms. Therefore it is not necessary for the CMS to have form support.

Search

Given the w3.org site is so huge and content is managed in a number of different systems, any out-of-the-box CMS search is not going to be effective. During the user research phase, we had user feedback that the current search is not very effective and is not well used. Some users noted it would be useful to search specifications content in particular.

At present w3.org links to a DuckDuckGo search page. DuckDuckGo do not offer any commercial branding options and do not allow sites to embed their search results in their own pages.

Search can be really important to users, though clear navigation should help users in the first instance.

Given the size and scope of building a search for w3.org we recommend this is reviewed and tackled as a separate project.

At present we can either keep the DuckDuckGo site search or remove search entirely. Given this links to a 3rd party site it could be argued users are savvy enough to use their own preferred search if they wish to.

Within this project we plan to retain a search for specific sections of your site (as they have now):

- Search News

- Search Blog

- Search Technical Reports

We do not plan to build a search to search across general page content, due to the scope of doing this properly.

Things to consider for a future search project:

- Do you want a dedicated search for specification pages? This would help users find specific details quickly.

- If you have a site search how do you judge relevance and prefer up-to-date content over archived content?

- Do you need to support multilingual search, so users can find content in their preferred language?

- Commercial search engines are good at judging relevance based on real-world usage (e.g. Microsoft Bing Custom Search)

- Another alternative is an open source tool such as Elasticsearch. This would be easier to refine to your exact requirements, though would require more development work.

- We would also recommend user testing to help understand how users want to use search.

CMS platforms

The CMS industry is huge, with 1000s of different software solutions available. Studio 24 has worked with a range of CMS software over the past 20 years, including WordPress, Drupal, and ExpressionEngine. We’ve also built two different custom CMS software platforms in the past, so we are experienced in the architectural needs of content management.

Licensing models

Open-Source

Platforms that have an open-source license to use freely, without commercial charge for the use of the software itself. Such platforms attract large, productive, and helpful communities and often have a reputation for proactive and effective security teams.

Contrary to this, large open-source projects that have existed for many years can suffer from older architectures which are difficult to update or can slow down community development. Arguably, the same can be said of commercial software, it’s just less obvious since they don’t work in the open.

W3C has a strong preference for an open-source license for the CMS platform.

Commercial

Platforms with a charged license fee, either one-off, recurring or a combination of the two. Commercial CMS platforms range from large, expensive, enterprise CMS platforms to smaller, more agile commercial software. Commercial software rewards developers for building software which they can invest back in the software, whereas open-source software has to rely on commercial sponsors or the efforts of the community.

Commercial software is also closed software, so it has less community and external peer-review. The common argument that open-source is inherently less secure is not valid, since community experts can peer review open-source code, something that is not possible with closed source code.

We will consider commercial software that fits the requirements for W3C.

Software-as-a-service (SaaS)

A hosted service that you pay a recurring fee to use. Such CMS platforms often either build a static site or provide an API to deliver content to the front-end. The advantage is you don’t need to worry about hosting or updating software for the CMS platform, it just works.

Netlify is currently used as part of the infrastructure for the WAI website, it is used for site previews. Another example of SaaS is a Content Distribution Network (CDN) to help cache static assets.

W3C plan to host and manage the CMS platform themselves, however, we may consider SaaS platforms to assist in specific areas for the new website.

Choosing a CMS

Given the flexibility of the hosting architecture of the W3C website, it is possible to support a range of different CMS types. We believe the right choice is dependant on a few factors:

- How well the CMS meets W3C’s key requirements.

- How good a fit the CMS to develop this project for Studio 24, so we can meet W3C’s business goals for this project.

- Ease of maintenance for the W3C Systems Team in the future, including how straightforward the CMS makes adding new sections or pages in the future.

Assessment questions

The following is a list of questions we’ll review when assessing CMS software.

CMS software

- Open source or commercial license?

- Is this a mature software product, ideally, one that has at least 2-3 major versions?

- How large is the community?

- Is the CMS under active development?

- What’s the quality of documentation?

- What are the technical platform requirements (PHP is preferred)?

- What security credentials does the CMS have? Do they have a security team?

Content editing

- Intuitive content editing

- Support for content fields and flexible components to build content

- Does it support a simple workflow for editors (who cannot publish) & publishers? Can this be set on a section-by-section basis (e.g. news)?

- When two users are editing content does the CMS lock content to help avoid two people overwriting each other’s work?

- Can each piece of content have a created date and a last updated date, to help show users how up-to-date content is?

- What options exist to manage personalized content (e.g. content for logged-in users, content for public users)

Internationalization

- Does it support translated page content (e.g. translated version of About page)?

- Does it support local content (e.g. local news article that does not exist in English)?

- What are localisation management tools like?

Front-end

- Does it have a flexible templating system?

- What options does it have for front-end performance (for content page delivery)?

- Does it support static site building?

- Does it have any features that make full-page caching a problem?

- What personalization options exist, can this work alongside Varnish full-page caching (e.g. via Vary HTTP headers)?

CMS features

- How accessible are the CMS editing tools?

- Does it support LDAP or OAuth authentication for logging into the CMS?

- Does it support two-factor authentication for the CMS editor login?

- Does it support versioning? How far back can this realistically go?

- Does it support storing content in Git?

- What options exist to integrate with 3rd party systems?

- Can you write plugins (if so, in what programming language)?

- Does it support dynamic functionality on the front-end (e.g. forms)?

- Does it support a content API?

The following is a summary of different types of CMS and a few examples of what Studio 24 plan to test and investigate. After the CMS testing work we will report back with our recommendations on what CMS platform to use for this project.

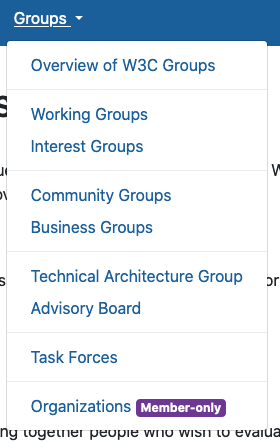

Monolithic CMS

A monolithic CMS is one large system that both manages content and delivers content, usually via web pages, to the end-user. It is a myth that monolithic systems are an inherently bad architectural design, though it is true many CMS platforms are large and bloated systems that can be difficult to work with.

The advantage of one system to do everything is that you can leverage the power of the CMS, and any community plugins, to manage content and customise how that content is displayed. An all-in-one system is usually simpler to maintain and use for the end-user.

The advantages of this approach are:

- Common software pattern so well understood and it’s how most CMSs work.

- Simple architecture so easier to host and maintain.

- Most CMSs have a huge range of plugins that can give you functionality for free (or very low cost). On the contrary, many plugins can be bloated or not quite do what you want.

Disadvantages of this approach are:

- Often slower performance. Full-page caching can help alleviate this.

- Due to the large volume of code this can present a security risk (though large open source projects have excellent security teams). It’s really important to keep on top of software updates to help combat this.

- Large, older CMS platforms can be unwieldy and present difficulties in custom development.

Typical architecture for a monolithic CMS:

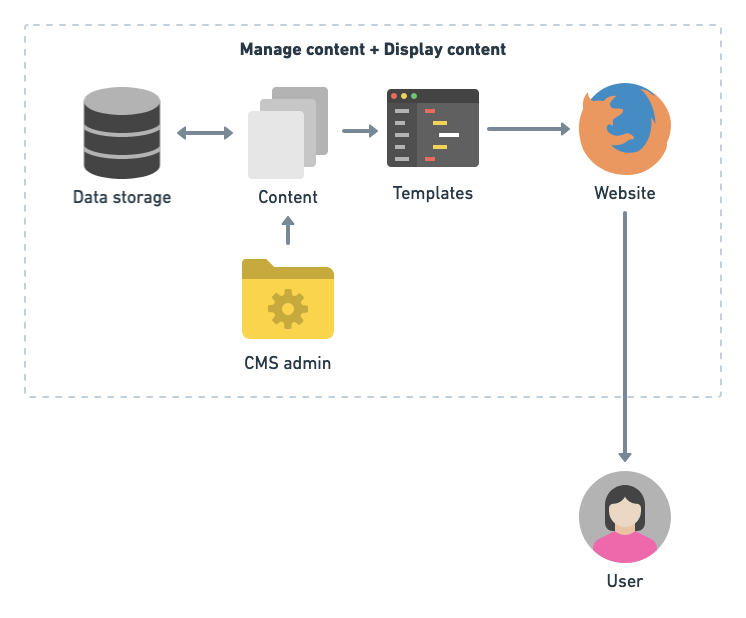

Headless or Decoupled CMS

The key difference with a headless CMS is that the front-end, which displays web pages is decoupled from the back-end, which manages web content. Content is managed in a CMS that only takes responsibility for content management. A separate system, for example a static site generator or custom code, is used to build the front-end.

It is very common in the industry for a JavaScript single-page application (SPA) to be built for a headless CMS powered site. Studio 24 does not believe this is an appropriate way to build content-based sites and certainly not for W3C. If a headless CMS approach is used for W3C, Studio 24 will ensure content is delivered via standards-based HTML.

The advantages of this approach are:

- A very clear separation of concerns.

- Build only what you need on the front-end, better for performance and security.

- Approach is designed to work with multiple content sources. By decoupling it also helps you deliver your content in multiple ways, if this is required (i.e. different channels)

- Protects you from legacy CMSs, since you can swap out the CMS platform without major changes to the front-end. With a monolithic CMS changing the CMS normally requires a complete rebuild on the front-end.

Disadvantages of this approach are:

- You cannot leverage any CMS code or CMS plugins to build the front-end.

- Front-end tends to be custom development, due to limited range of front-end software for Headless CMS sites. This may be considered a risk compared with more standard approaches.

- All content must be exposed via an API (with custom code you can integrate with other types of content sources).

- Can create a more complex development setup, however, if done well can simplify front-end development due to the separation of concerns.

- Therefore, you have to reinvent standard functionality a CMS would offer out of the box, including pagination, templating, navigation.

- Smaller community to support software, since front-end is custom.

Typical architecture for a headless or decoupled CMS is split between managing content and delivering content:

Headless CMS and open source Symfony tools

Studio 24 blogged about Headless CMS in Dec 2018, and we’ve developed a number of client sites based on Headless CMS technology, including Crown Commercial Service and Flora & Fauna International. We have worked on an open source project called Strata using the Symfony web framework to help build headless CMS sites.

If there is a desire to build the front-end in Symfony along with a Headless CMS, we would recommend using our tools to assist with this. However, please note Strata is around 1.5 years old as a project and is under active development. Studio 24 is committed to this project as a strategic aim of the business, however, this approach also represents a risk. If W3C want to only use well-established software with larger communities then we would not recommend this approach.

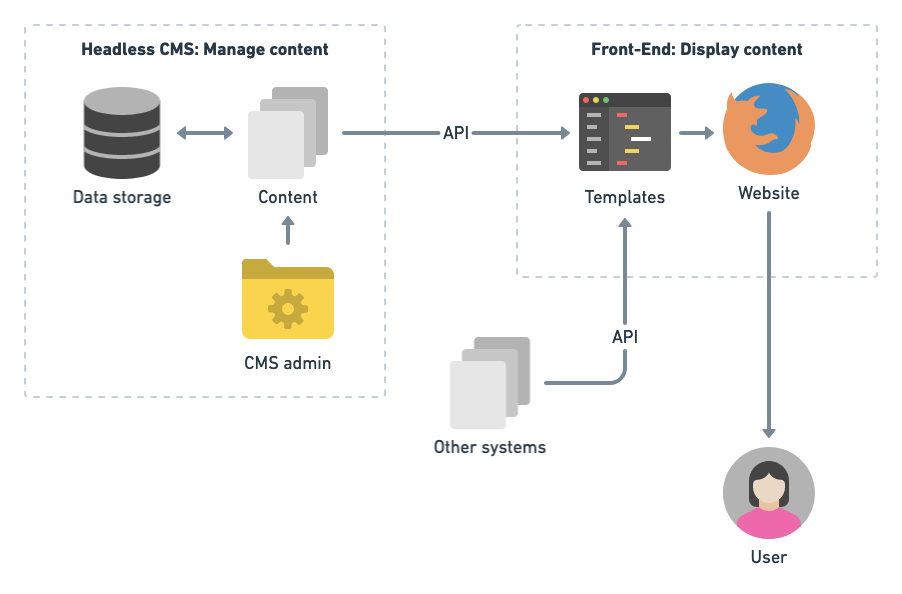

Static site generator

A popular current method of publishing website files is a static site generator. This type of CMS does not use a dynamic programming language to deliver content to users, instead content is pre-built as static HTML and delivered as pure HTML.

This has a huge benefit on performance since you really can’t get much faster than static HTML. However, the key drawback is you cannot have any dynamic content on static pages without the use of JavaScript. For example, common things that are harder with static pages include form submission, search, pagination.

The advantages of this approach are:

- Very fast performance.

- Good security, since no dynamic code.

- Easy to host (it’s just HTML)

- This approach is already used by the WAI website

Disadvantages of this approach are:

- Can be more complex to setup and maintain than a traditional CMS.

- Only supports static content, any dynamic content is harder to achieve (e.g. forms).

- Many static site generators only support Markdown rather than more complex content editing (this can also be seen as an advantage depending on your point of view).

- Smaller communities to support software.

Typical architecture for a static site generator is split between the CMS to manage content and the static site generator to build content into HTML pages for the front-end:

What Studio 24 deliver

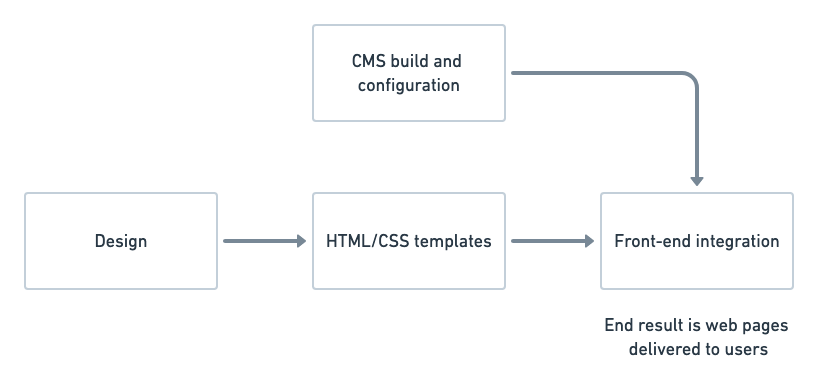

On a traditional web project Studio 24 design a site, create HTML/CSS templates based on this design, build and configure the CMS, and integrate these all together to create the front-end web pages that deliver the site.

For the front-end integration stage, due to the volume of pages on w3.org, Studio 24 and W3C will need to review the planned pages to launch with and agree which Studio 24 build and which W3C build. W3C have noted they are happy to take on the majority of front-end integration if this is initially setup and documented by Studio 24.

Studio 24 plan to build out a set of core pages fully integrated with the CMS, provide documentation on how to do this for new pages, and work with the W3C Systems Team to ensure enough pages are built out for launch.

The web pages Studio 24 will fully build out will be decided based on priority and budget. It is expected W3C will assist in integrating some core web pages to help ensure we have enough pages in the new design for launch.

In addition, there are a number of 3rd party systems that W3C manage in Symfony, such as the TR index page and Groups pages. W3C will be responsible for integrating the new HTML templates with these systems and Studio 24 will offer support.

At present it is not expected that other tools, such as Mediawiki, would be updated in the new design. Other such external systems will need to be judged on a case-by-case basis to evaluate whether it’s worth updating the HTML templates.